News, articles, and interesting stuff from the College of Business

Finance faculty researcher’s findings are at the forefront of the disclosure debate

In his latest research, Gibbons explores the costs and benefits of increased regulations for environmental and social disclosures. One out of every three invested dollars in the United States now has an objective attached to it rather than just making maximum profits.

Before he was the Stirek Assistant Professor of Finance at Oregon State, Brian Gibbons was a doctoral student at Penn State.

A fortuitous connection between Gibbons, a former stock analyst, his office mate, and his office mate’s spouse, a former Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) economist and current Penn State professor, brought him to Oregon State University.

The three ended up talking about corporate governance and information economics. The Penn State professor was collaborating with another former SEC economist, Jonathan Kalodimos, an associate professor of finance at the College of Business.

Kalodimos was using the SEC’s Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis and Retrieval system (EDGAR) — the government database containing all disclosure reports for public companies in the United States. — for a research project that involved stock analysts.

“Being a former stock analyst myself, I was helpful to their project,” Gibbons said.

Soon they were collaborating on research, leveraging Gibbons’ experience while Kalodimos showed Gibbons how to tap into big data contained in the EDGAR database.

Essentially, the SEC publishes partial IP addresses of search queries to these public filings, which Gibbons and Kalodimos traced back to the institutions that were doing the searching. The researchers sorted through this web traffic data to show how companies, stock analysts and investors utilize companies’ published disclosure information. This method has enabled them to identify promising research projects.

“It was like having a hammer and then finding nails,” Gibbons said.

In his first two published studies, Gibbons examined how information from the EDGAR database is used by analysts and venture capitalists. In the first paper, Gibbons showed that when stock analysts access financial disclosures, they are able to provide more accurate and impactful insights to people who listen and follow their recommendations.

In the second paper, Gibbons looked at patterns in the filings accessed by venture capitalists. He found their searches were predictive of what happened to the companies they invested in.

“Because the information is available to everyone, it was not obvious that someone using this information could gain an edge over others. Our research shows that some people are quite skilled at interpreting this information and turning it into useful outputs,” Gibbons said.

Five years after meeting Kalodimos, Gibbons became a colleague, and they continue to collaborate.

In his latest research, Gibbons explores the costs and benefits of increased regulations for environmental and social disclosures. One out of every three invested dollars in the United States now has an objective attached to it rather than just making maximum profits.

“People want to make decisions with their money that have impacts on society,” Gibbons said. “But they don’t always have the necessary information to make those decisions.”

While more than 30 countries have regulations that mandate the disclosure of either environmental or social information or both, the United States does not. With social and environmental disclosures voluntary, companies aren’t always forthcoming with facts, and some provide misleading information to appeal to would-be investors — a practice known as greenwashing.

Establishing a set of rules around environmental and social disclosures is among the top priorities of U.S. financial regulators.

What will the finance sector’s role be in transformation?

While politicians debate whether financial disclosures are too intrusive or don’t go far enough, Gibbons’ new research shows that having verifiable information can be used to make informed investing decisions.

Based on countries that require environmental and/or social disclosures, Gibbons research shows that when investors have access to additional information, they act on it.

“Certain types of disclosures matter,” Gibbons said. “Investors who want this type of information are changing their investment patterns by increasing ownership in companies required to disclose.”

These changes have feedback effects on the companies themselves.

“When investors are focused on the long-term, managers of these companies also focus on the long-term,” he said.

A finalized rule for U.S. environmental disclosures is expected soon but likely will face legal challenges, Gibbons predicts. So, implementation could be delayed for several more years or even be blocked by the courts.

Regardless, Gibbons is excited that his research is at the forefront of current policy discussions.

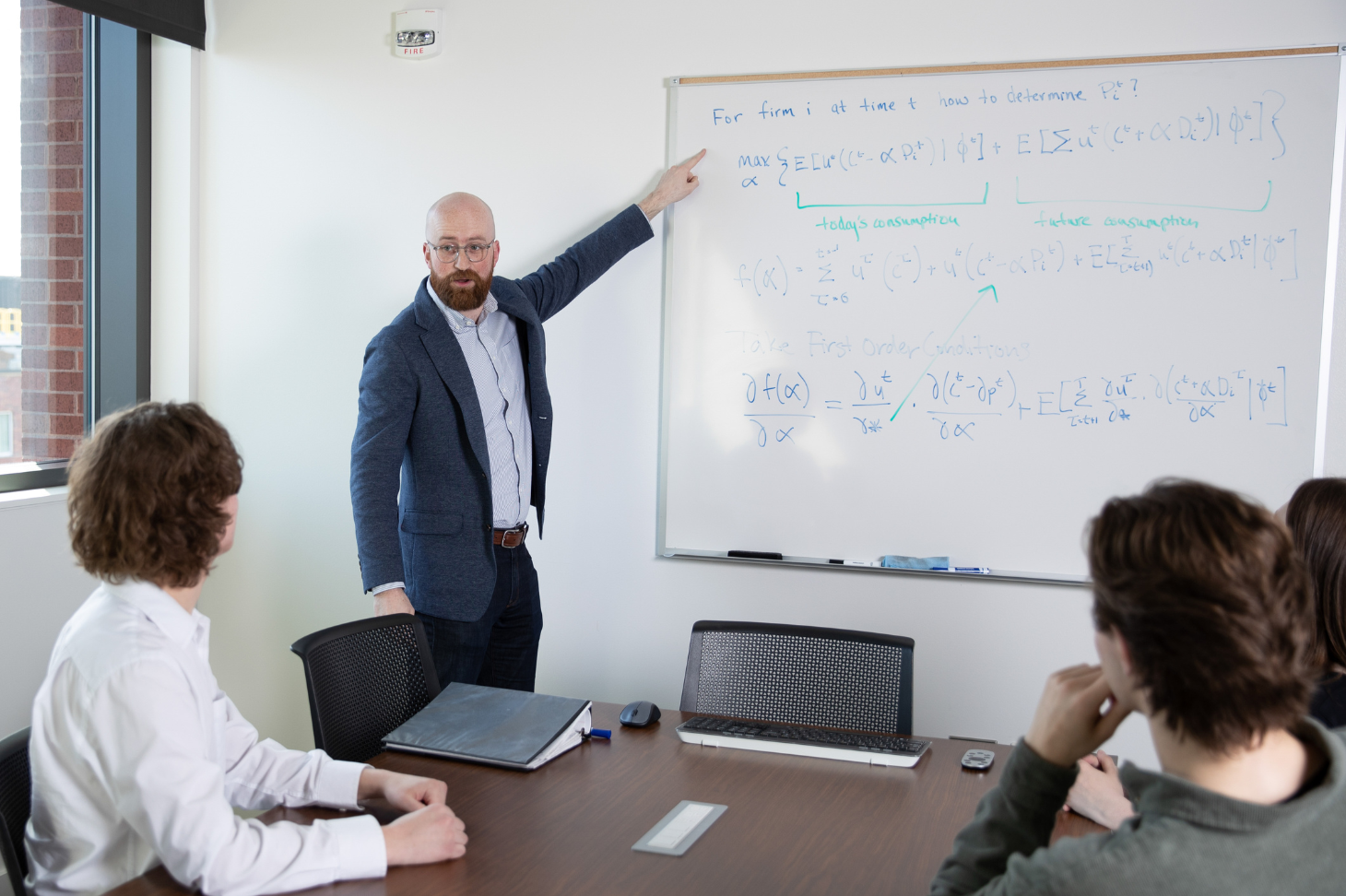

Although research is what interested Gibbons in the position in the College of Business, he’s found the balance between teaching and research to be fulfilling. He teaches an introductory finance class as well as an advanced course in corporate finance.

“I love both teaching and research,” Gibbons said.

In the introductory course, which is required for all business majors, Gibbons knows not all his students will become stock analysts. So, he tries to spark excitement about the topic, while giving students the basics of finance that are applicable to life in general. He also encourages his students to create a music playlist that they listen to while working on problems.

“We have to work hard, do the math and learn the basics,” he said. “But I try my best to make the environment a little more engaging.”

Learn more about endowed faculty and the College of Business’s research enterprise on our website.